By Violet Auma | violetmedia8@gmail.com

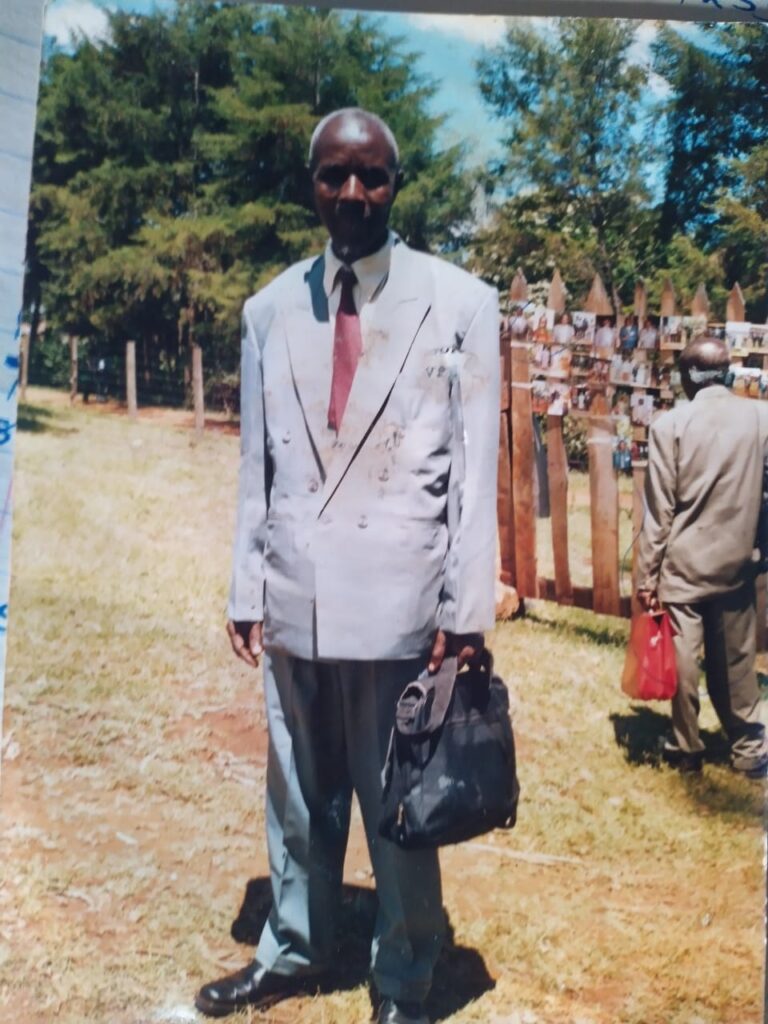

Five years have passed since Reverend Hezekiah Mavisi took his final breath and five months since his wife, Grace Mavisi, followed him, her heart weary from a battle she could no longer fight.

On 11th November 2020, Reverend Mavisi died at the age of 84. The family began preparing for his burial. But before they could even dig a grave —a sacred act in Luhya culture reserved only after a body arrives home, police arrived with a court order stopping the burial. A day his younger son, Philip Mavisi remembers vividly.

“I had gone to buy jembes and spades,” Philip recalls softly. “Then I received a call that police were here. I thought it was about COVID rules, but it was the land again.”

For the next four years, Grace Mavisi, a devoted church leader fondly known as Mama Assembly at the PAG Church, bore the pain in silence. Her husband’s unburied body haunted her prayers and her sleep.

“She cried every day,” says Philip. “She kept saying, ‘I just want my husband buried before I die.’”

On 2nd May 2025, Grace died at the age of 82. The family believes stress killed her.

“If the county had allowed us to bury Dad, Mum would still be alive,” says Philip. “She just lost hope.”

Yet the earth that once carried their footsteps now refuses to receive them. Their bodies lie in cold drawers at the Vihiga County Mortuary, trapped between death and justice, prisoners of a land dispute that has denied them a final resting place.

At their home in Mutembe village, Mbale, time seems frozen. The walls of the once-vibrant homestead are cracked and fading.

The compound, once alive with hymns and laughter, is now overrun by weeds. The air is heavy, thick with silence and sorrow. A silence that speaks of years of mourning without closure.

According to his son, Philip Mavisi, the last born son of the late Ondego he says that the land belongs to his father and not the county government.

For the Mavisi family, each sunrise brings the same anguish. The father’s body has remained at the mortuary since 2020. The mothers’ since May 2025. The family says they have been denied the right to bury them on their ancestral land, the only home they have ever known.

“We just want to bury our parents and find peace,” says their youngest son, Philip Mavisi, his voice trembling. “Every time we visit the morgue, it feels like reopening a wound. My father’s body has deteriorated, and my mother’s is still waiting beside him. We are dying inside, he said during an interview with Shahidi TV.

The dispute dates back more than two decades. In the early 2000s, the then Vihiga Municipal Council identified land around St. Claire’s Girls High School for expansion. Several families, including the Mavisis, were promised alternative land in Lumakanda, Lugari Sub-County.

In 2001, Reverend Mavisi and his eldest son travelled to inspect the new land. But the visit turned violent.

“They were attacked and chased away,” recalls George Mavisi, one of the sons. “My father was cut on the head, and my brother’s leg was broken.”

“In our Luhya tradition, we cannot live on land where blood has been shed. That’s how the family rejected the exchange.” Philip added.

The family stayed on their 2.4-hectare ancestral land in Mutembe. But in 2017, trouble resurfaced. After selling a small portion of the land, they received an unexpected eviction order giving them two weeks to vacate, during the tenure of former Governor Moses Akaranga.

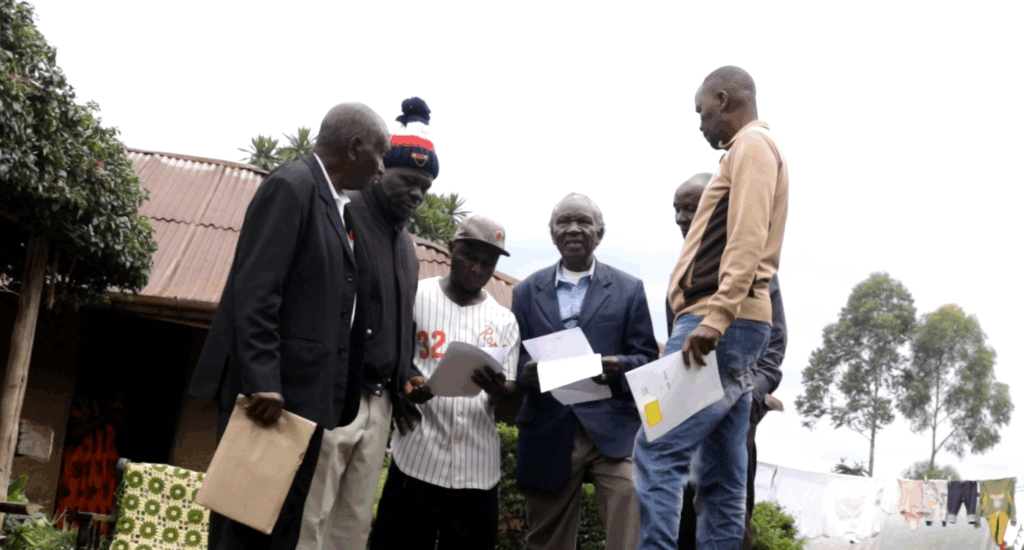

They refused, insisting they held valid title deeds.

Now, both bodies remain at the Vihiga Mortuary, as the family drowns in nearly one million shillings of accumulated mortuary fees, a bill growing by Sh700 per body per day.

Under Maragoli tradition, a wife cannot be buried before her husband. The family insists the two must be buried together, or the husband first.

“If we bury Mum before Dad, it will curse the family,” warns Rachael Mbashio, wife to the eldest son, who was disabled in the 2001 assault. “We even dream of them asking why we’ve left them in the cold.”

The Mavisi homestead, once a gathering place for prayer and song, is now shunned. Some neighbors whisper that the family is cursed. Others avoid them altogether.

“We no longer attend funerals or celebrations,” says Margaret Ondego, a relative. “How can we go to bury others when our own lie unburied?”

The family maintains that their land documents are genuine, inherited from their father and duly registered. They accuse unnamed county officials of eyeing their prime land located near the governor’s and county commissioner’s offices.

“If the county wants this land, let them come and buy it,” says Philip. “We’ll move within Vihiga, but not to Mautuma forest where others were dumped.”

Vihiga County Attorney Aggrey Musiega dismisses the family’s claim of ancestral ownership, insisting the land was lawfully acquired by the government decades ago.

“They cannot talk of ancestral land,” he says. “Back in 2015, we issued them with a notice after establishing that the parcel was part of land compulsorily acquired to create the former district headquarters. That was government land, earmarked for other development projects.”

According to Musiega, the affected families were compensated and offered alternative land in Lugari, but later returned after the government failed to secure the property immediately.

“When Reverend Mavisi died, we sought clarification from the court, and the court ruled that he should not be buried there,” he explains.

On allegations of double allocation of the alternative parcel in Mautuma, Musiega distances the county government from the controversy, saying it is beyond their mandate to confirm whether such an error occurred.

“It was done by the national government through the then Vihiga Municipal Council in 1992,” he says. “It’s not within our capacity to know those details. I’m not their lawyer.”

He insists the family should surrender their title deeds, which he claims are invalid.

“The best thing they can do is to hand over those titles,” says Musiega. “We have already served them with eviction orders. They should vacate peacefully, go to court, or we’ll proceed with eviction. It is not the county’s responsibility to identify where they will bury their people.”

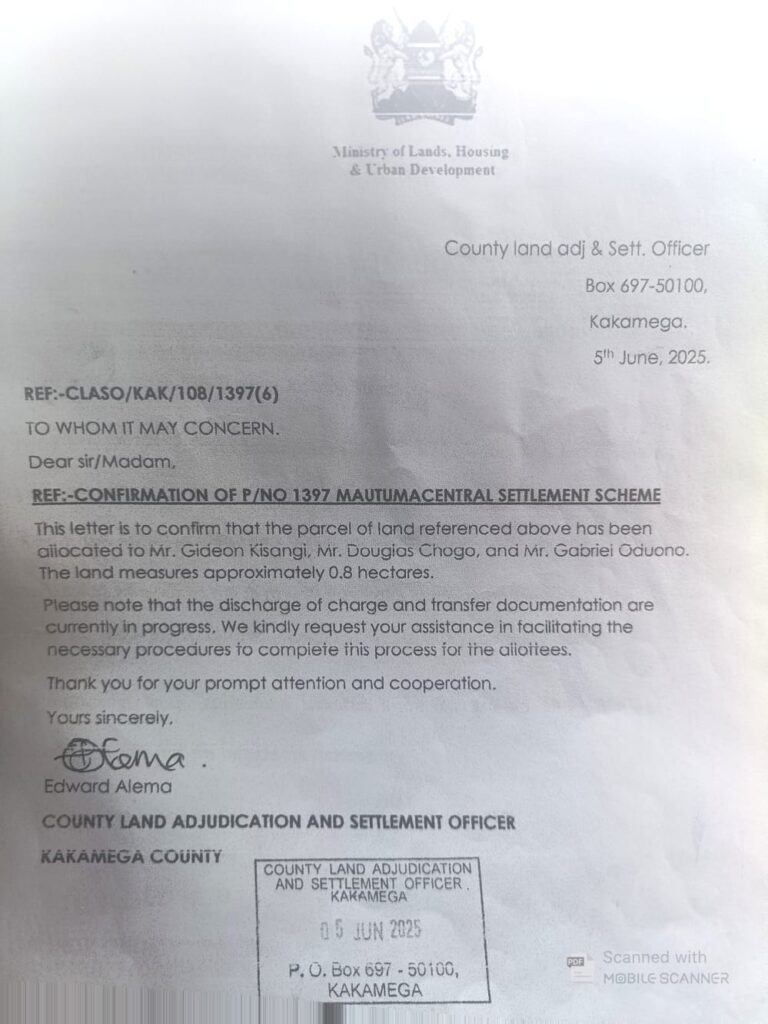

However, a land adjudication report dated June 5, 2025, seen by SHAHIDI TV, appears to contradict the county’s position. It shows that the supposed alternative land in Mautuma Settlement Scheme, parcel number 1397 is already occupied by three individuals: Gideon Kisangi, Douglas Chogo, and Gabriel Oduono, and measures less than one hectare, far smaller than the Mavisi land in Mutembe.

The Mavisi family’s ordeal is not an isolated tragedy but part of a broader crisis gripping Vihiga County.

Land has become the county’s most contested and emotional asset, its scarcity turning every boundary into a potential battlefield.

A recent University of Nairobi study found that more than half of households in parts of Vihiga, including Lusengeli and Esianda, live on land without title deeds. Most of these parcels are family inheritance plots, handed down orally and often subdivided until they are barely large enough to sustain a home.

The same study found the average farm size to be just 0.41 hectares, less than an acre, making Vihiga one of the most densely settled counties in Kenya.

Vihiga also ranks among the top counties nationally in unresolved land cases. Recent data show that more than 80 percent of households have been affected by boundary or succession disputes, while many others are fighting cases in the Environment and Land Court in Kakamega, a backlog that continues to grow each year.

The Vihiga County Integrated Development Plan for 2023-2027 acknowledges this crisis, warning that the absence of a land-use policy, widespread unregistered plots, and unplanned settlement patterns are fueling tension and environmental degradation.

It calls land conflict one of the biggest barriers to development in the county.

It is within this volatile environment that the Mavisi family’s pain unfolds, a human face to a countywide struggle where ancestral attachment, bureaucracy, and power collide.

Maragoli cultural elders say the Mavisis’ case is no longer just legal, it has become a spiritual wound.

“Denying burial is not only unjust but dangerous,” says Samuel Muindi, Coordinator for Maragoli Culture. “It angers both the ancestors and the spirits. Reverend Mavisi served God for 40 years. He deserves dignity in death.”

As President William Ruto prepares to visit Vihiga County, the Mavisi family has one plea:

“Mr. President, please help us bury our parents,” says Philip. “You are a Christian. My father was a pastor. Hear our cry.”

Six years on, the Mavisi home remains suspended in grief, the grass uncut, the air heavy, the laughter long gone. Two bodies lie in cold drawers, waiting for earth that refuses to open.

Until justice comes, the family of Reverend and Grace Mavisi will continue to live between mourning and memory, a family punished by the very land that once defined their lives.