By Violet Auma | violetmedia8@gmail.com

“Push… push… the baby is coming.”

The nurse’s voice was calm but urgent.

Sweat clung to her forehead, and her fingers dug into the hospital sheets as if letting go would mean losing everything. The delivery room smelled of antiseptic, mixed with the sharp tang of fear.

Monitors beeped steadily, punctuating the heavy silence. Her heart raced in rhythm with the faint heartbeat flashing on the screen.

Minutes stretched into eternity. She pushed again. Her legs trembled. Another wave of pain surged through her body.

Then, finally, the moment she had imagined countless times, but it was nothing like she expected.

The baby emerged, tiny and fragile, eyes closed. Nurses lifted the infant toward her chest. The room waited for the first cry—that piercing, life-affirming sound that announces a new beginning.

The golden 60 seconds passed.

Nothing.

She stared blankly at the ceiling, unmoving. The nurses whispered that she was in shock, but inside, she felt only emptiness—fear, confusion, and numbness tangled together. The baby’s chest rose and fell with the help of oxygen.

“The baby will be fine,” one nurse whispered.

In the hours that followed, the young mother, whom we will call Sarah to protect her identity, retreated inward. The baby’s cries, especially at night, felt like accusations. She recoiled at the closeness, unable to breastfeed, unable to smile.

“Be strong… you’ll get used to it… other girls manage,” the nurses urged.

She nodded. She smiled faintly. But the heaviness in her chest never lifted.

Sarah is 18 years old. She had completed Form Four the year before, her dreams of flying planes and finishing school suspended indefinitely.

Unlike many mothers who meet their babies with joy, Sarah’s entry into motherhood was shaped by trauma. She had been sexually abused by a cousin who threatened her into silence. The pregnancy became a living reminder of betrayal.

When her baby was placed beside her in the delivery room, she did not cry. Her withdrawal, loss of appetite, and emotional numbness were dismissed as stress and hormonal changes.

For months, she battled guilt, shame, and anxiety. Sleep brought nightmares. Daytime brought detachment from the world, from her child, and from herself.

Only when her mother found her sitting alone in the dark, tears streaming silently down her face, was help finally sought.

Counseling gave a name to her suffering: postpartum depression.

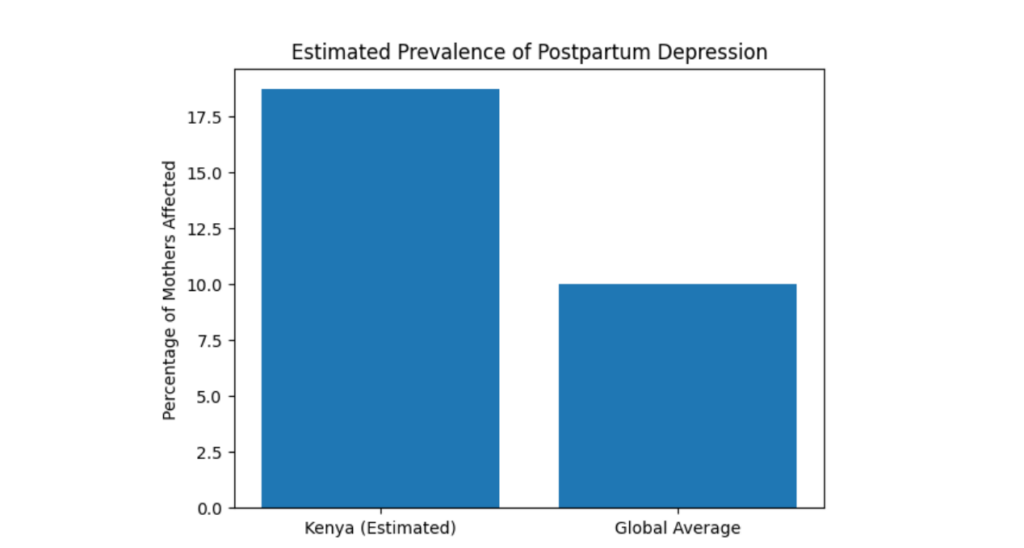

According to UNFPA and local health experts, postpartum depression affects an estimated 18.7 percent of Kenyan mothers nearly double the global average, with even higher rates among adolescent mothers in rural counties like Kakamega.

Estimated prevalence of postpartum depression in Kenya compared to the global average. Kenya’s burden is significantly higher, driven by adolescent pregnancies, birth trauma, sexual violence, and limited mental health services.

Estimated prevalence of postpartum depression in Kenya compared to the global average. Kenya’s burden is significantly higher, driven by adolescent pregnancies, birth trauma, sexual violence, and limited mental health services.

“I felt trapped in my own body,” Sarah says. “I wanted to love my child, but I couldn’t. I didn’t know who I was anymore.”

Adolescent pregnancies in Kenya remain a major public health challenge.

According to national data, in 2023 alone, more than 250,000 pregnancies were reported among girls aged 10 to 19 years. Each number represents a girl whose life has been transformed or derailed by early motherhood, with profound implications for her health, education, and mental wellbeing.

For 17-year-old twin sisters in rural Kakamega, the struggle became unbearable. They dropped out of school in Form Three after their paternal uncle impregnated both of them, just weeks apart.

One of them, whom we will call Anita, recalls the manipulation: “He gave me 50 shillings to buy mandazi. Then it turned abusive. I didn’t understand at first. I just wanted to go to school.”

When hospital tests confirmed her pregnancy, her mother collapsed.

“She had a mental breakdown,” Anita says. “She was completely lost.”

While still hospitalized, Anita went into labor. After hours of agony and complications, she was rushed into surgery. When she regained consciousness, a nurse briefly showed her the baby.

“See your baby boy.”

He cried.

“That cry still rings in my mind,” she says. “Every time I sleep, I hear him.”

She was not allowed to hold or breastfeed him.

At the same time, her twin sister was also in labor. Both had been impregnated by the same man—their paternal uncle. The second twin describes how he groomed her, taking her to clubs, slipping alcohol into her drinks, offering money she had never seen at home.

Health workers placed both babies in children’s homes immediately after birth. The surgical scars on the sisters’ bodies remain the only proof that they were ever mothers.

Because the pregnancies resulted from incest, family elders warned that bringing the babies home would bring misfortune, madness, or death. Fearful of cultural backlash, the family complied.

The babies are now five months old, living in nearby children’s homes.

“Every time we pass there, we remember,” one sister says. “They are growing without us, but still they are products of incest and abomination.”

Their father severed all contact. Financial support vanished. Threats from the perpetrator’s relatives escalated.

The psychological toll was devastating.

“I once stood in the middle of a busy highway waiting to be hit by vehicles,” Anita admits. “My grandmother, who was secretly following me, rescued me.”

Her twin attempted to drown herself in a nearby river. Both survived.

“There are days I just wish I wasn’t here,” Anita says. “Especially when my former schoolmates laugh at me.”

“We don’t leave the house anymore. We lock ourselves inside all day.”

A defilement case was reported, but the suspect disappeared. More than a year later, justice remains elusive.

Medical experts say the twins’ experiences represent an extreme but not uncommon pathway to postpartum depression and psychosis, especially among adolescents exposed to sexual violence, forced separation from their babies, stigma, and unresolved legal trauma.

“These mothers go through different levels of psychological torture,” says Dr. Samuel Kamoche, psychiatrist at Kakamega County Referral Hospital. “Some withdraw. Some become suicidal. Some lose touch with reality.”

According to UNFPA, routine postnatal mental health screening remains rare, even as Kenyan girls continue to experience pregnancy and childbirth under profoundly stressful conditions.

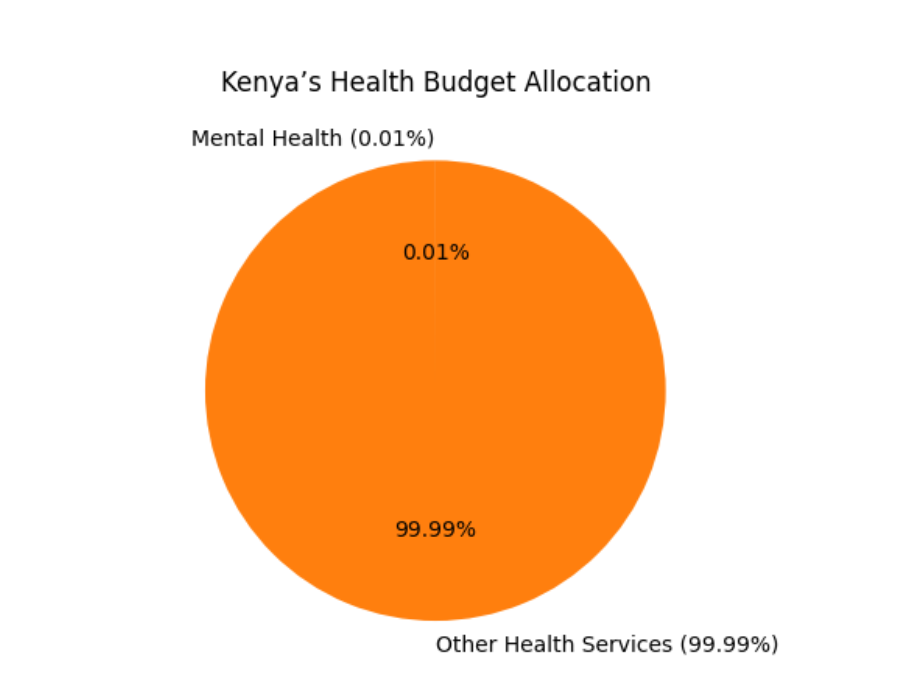

Mental health receives just 0.01% of Kenya’s health budget, leaving mothers with postpartum depression largely unsupported.

Mental health receives just 0.01% of Kenya’s health budget, leaving mothers with postpartum depression largely unsupported.

Adding to the challenge is severe underfunding of mental health services in Kenya. Official audits show that just 0.01 percent of the national health budget is allocated to mental health far below 5% global recommendations.

Experts note that such underinvestment leaves counties with too few specialists, inadequate facilities, and little capacity to screen and support mothers, particularly after delivery.

“The system has failed these girls,” says Phillis Lumwaji, a local human rights activist. “We have hospitals, we have clinics, but nobody is listening to their cries for help.”

For many mothers like Naomi, postpartum distress emerges from medical crises rather than abuse.

At 24, married with one child at home, Naomi was rushed to Kakamega County Referral Hospital at 2 a.m. when labor pains intensified. Her second child, Eunice, was born prematurely and failed to cry within the golden minute. She was rushed to the neonatal unit and placed on oxygen.

Naomi became withdrawn and disoriented. Within days, she refused to touch or breastfeed her baby. She was admitted to Ward 9, the hospital’s mental health unit, diagnosed with postpartum depression triggered by birth trauma.

“She collapsed emotionally,” says Dr. Mike Ekisa, in charge of the Young Mothers Unit. “At this stage, hormones are extremely high. When trauma occurs, depression can be severe.”

Nurse Eileen Muhavi from the newborn unit says nearly half of preterm babies in Kakamega County most of them born to teenage mothers, struggle with breathing problems, a reality that echoes across Kenya.

Naomi’s husband had to split his time between hospital visits, looking after their two-year-old left with a neighbor, and earning a living showing just how much postpartum distress can strain an entire household. Postpartum depression remains a silent but serious mental health burden for women of childbearing age.

“I spent a lot of money buying powdered milk and diapers for the newborn. I have to work long hours, check on my older child at home, and also come see my wife and baby at the hospital. I have to be here on time to feed the newborn. She’s just a few days old, but she’s feeding through a tube in the incubator,” Sebastian said, his voice heavy with emotion.

Kakamega County has only two psychiatrists, far below what is needed.

“If the baby survives, recovery is often faster,” explains Dr. Kamoche. “But when the baby dies or is taken away, many mothers sink into major depressive disorder.”

Adolescent pregnancies, sexual abuse, unplanned births, family conflict, and complicated deliveries all increase the risk of postpartum depression. Yet mental health assessments are rarely integrated into routine maternal care.

In Kakamega, postpartum depression often hides behind obedience, smiles, and silence. Mothers who struggle are labeled lazy or ungrateful. Fathers absorb pressure quietly. Families fracture unseen.

Yet when support comes early, outcomes change. Counseling, family engagement, and timely intervention allow mothers to reconnect with their children and with themselves.

Motherhood does not erase trauma. It exposes it.

“No one should have to beg for help after giving birth,” says Dr. Ekisa. “These mothers deserve care, compassion, and a chance to heal.”

Stories like Sarah’s, the twins’, and Naomi’s reveal a system struggling to protect the most vulnerable. When depression is named, acknowledged, and treated, healing becomes possible.

Help should never be something a mother has to beg for. Joy, hope, and the bond between mother and child can be reclaimed, but only when the silence after birth is finally broken.