By Violet Auma

Kenya faces a growing cancer burden, with healthcare systems strained under the weight of treatment costs and the economic ripple effects of cancer related deaths. While government investments in healthcare like the KSh 104 billion spent on a Health digital superhighway signal hope, the challenges are immense.

These include foreseen implications of U.S. executive orders signed by President Donald Trump on global health funding and the enduring fight to reduce cancer fatalities.

In a country like Kenya, where cancer is now the third leading cause of death, with an estimated 42,000 new cases and 27,000 deaths annually, a lot needs to be done. These figures reflect the economic devastation when breadwinners fall sick or succumb to the disease, leaving families in financial ruin.

Judith Achieng’, a resilient woman in her mid-40s and a mother of six, epitomizes this struggle.

Until recently, she was a vibrant businesswoman in her Shirere village in Kakamega County, managing a thriving stall at the nearby Masingo market and keeping her household running smoothly. Life for Judith was busy but full of purpose.

That was until a small, persistent pain in her chest changed everything. At first, Judith thought it was nothing a passing discomfort she could ignore. But as days turned into weeks, the pain grew sharper, and a lump began to form in her breast. It was during an evening with her family, as she tried to lift her youngest child, that she realized something was truly wrong. The lump felt larger, and the pain had become unbearable.

It was then that her husband, a matatu tout, urged her to see a doctor. Reluctantly, Judith went to Kakamega Referral Hospital. That visit marked the beginning of an unexpected journey one that would test her strength and reshape her family’s life.

After examining her, the nurse requested further tests to be conducted at Oasis hospital.

“At Oasis, I was told the test would cost 28,500. I immediately informed my husband, who later took me to a herbalist. She gave me a full dose concoction, but there was no change. In fact, the lump continued to enlarge,” she said.

She later went to a different hospital, where she paid 18,000 for the test and was advised to return for the results in two weeks.

That was the first time Judith heard the word “cancer” in her family, it was already at stage three. The doctor explained that the lump in her breast needed urgent attention it was likely a tumor, and surgery was her best option.

“I felt like the world stopped,” Judith recalls. “All I could think about were my children. What would happen to them if I didn’t survive?”

It was around March, a time when doctors in public hospitals were threatening to strike. So, I began chemotherapy at a private hospital,” she said, tears welling in her eyes.

Judith underwent eight rounds of chemotherapy, each session reminding her of her determination to stay alive for her children. She was advised to ensure her National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF) contributions were up-to-date. With NHIF’s recent transition to a social health authority, the family was instructed to pay a year’s premium upfront. They pooled together all their savings to meet this requirement.

Months later, she underwent surgery. One of her breasts was removed to prevent the cancer from spreading further. When she woke up after the operation, the physical pain was matched only by the emotional toll.

“I felt like I had lost a part of myself,” Judith says softly. “But I kept reminding myself I’m still alive. My children still have their mother.”

Life after the surgery has been a struggle. Judith is weak and frail, still in pain from the stitches. She can’t lift heavy things, which means her stall at the market has been closed for months. The children, especially the older ones, have taken on more responsibilities, helping with chores and looking after their younger siblings.

Her husband, does what he can, but his earnings as a matatu tout barely cover the basics. There are days when the family goes to bed hungry. “I see the worry in his eyes,” Judith says. “He tries so hard, but it’s not enough.”

Judith’s story echoes across Kenya, from Kakamega County to Kwale County, over 700 kilometers away. Fear and stigma around cancer remain pervasive, but change is on the horizon.

In Kwale County, Mwanahamisi Salim, a mother of five, has today joined hundreds of women at Kinondo Kwetu Hospital for a free cancer screening. “I’ve seen women suffer from breast cancer here,” she says. “That’s why I decided to come for screening. If it’s detected early, it can be treated.”

Mwanahamisi had previously been screened for cervical cancer and was relieved to be clear. However, after seeing others diagnosed with breast cancer, she knew she couldn’t wait. “Many women here use herbal medicine and only go to the hospital when it’s too late,” she explains. “I urge all women to come for screening. It’s free, and early detection could save your life.”

Sentiments echoed by Patience Kanga, who says her decision was also influenced by the integration of AI technology in cancer screening, which promises faster and more accurate results.

“I saw posters about AI cancer screening on WhatsApp and traveled all the way from Lungalunga to get screened today,” she says. “At first, I was skeptical because of the fear that a cancer diagnosis means certain death. But after learning that AI provides immediate results, I decided to take the test.”

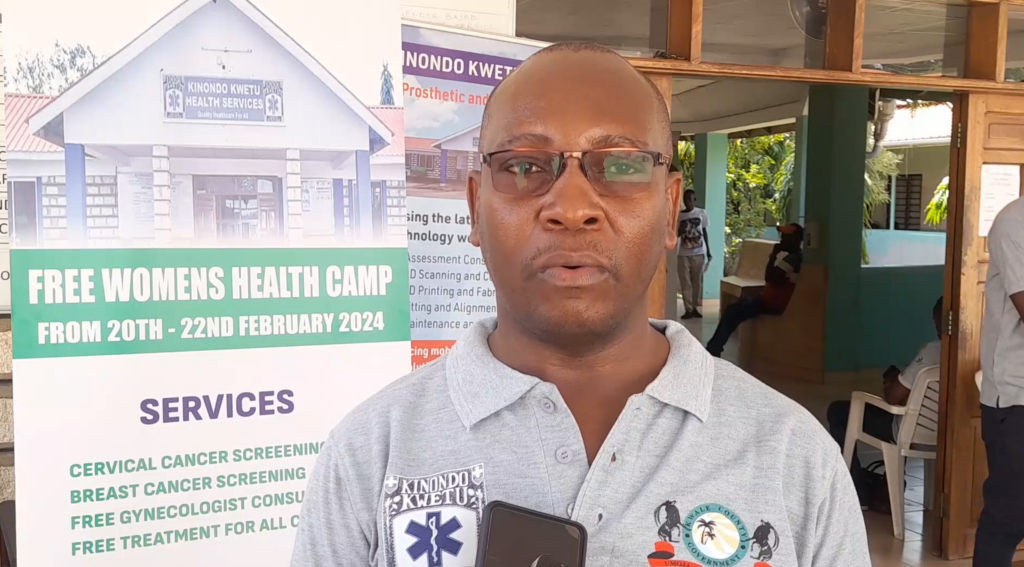

The future of breast cancer care in Kenya holds hope, with artificial intelligence (AI) paving the way for quicker, more accurate diagnoses. Harrison Kaingu, a medical laboratory scientist at Kinondo Kwetu hospital which has incorporated AI in breast and cervical cancer in diagnosis explains, “With AI, we can detect pre-cancerous cells before they develop into cancer. Initially, we used AI as a research tool, but now we’ve integrated it into patient care.” he added

For patients, the process of waiting for results after a mammogram can be excruciating. AI technology has the potential to speed up this process significantly, offering quicker results that could lead to faster treatment options. This could reduce patient anxiety and ensure that those diagnosed with breast cancer can begin their treatment journey without unnecessary delays.

Studies show that AI algorithms can match or surpass human radiologists in accuracy. For instance, a 2020 study published in Nature found that AI systems reduced both false positives and negatives in mammogram readings.

Kaingu reports that last year, 2.5% of women screened in Kwale were diagnosed with cervical cancer. Now aiming to change that narrative through early diagnosis and treatment using AI “Our focus on these cancers aims to improve women’s health using the best technology for better treatment and care,” he says.

Kaingu envisions AI as a partner to healthcare workers. “If you have 1,000 patients to screen, one pathologist can only do 20 slides a day. How long will it take to finish 1,000? With AI, slides can be digitized and stored for years, ready for retrieval and analysis whenever needed.”

According to the Health Ministry’s Deputy Director General, Dr. Sultani Matendechero, the government is already embracing artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare. “We recently conducted a pilot project on managing skin diseases using AI, which is now informing both domestic and global policies in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO). The same approach is being applied to cancer care,” he said.

Kenya is embracing AI’s potential “We have policies in place to guide its integration, and our ongoing studies will inform future frameworks.”

Dr. Matendechero emphasized the potential of AI to make specialized healthcare services more accessible. “As a government, we appreciate that AI is a tool that will make it easier for specialized services to be available even in underserved regions. With technology, we can connect our people with experts worldwide from Europe to the U.S to collaboratively interpret diagnoses and implement management strategies for patients.”

He also mentions the significant investments the Kenyan government has made to support digital health systems. “We’ve spent KSh 104 billion on a digital superhighway linking health information across the country. This infrastructure will enhance AI’s efficiency and accessibility.”

The Ministry Deputy Director General also noted the role of community health promoters in bridging the gap. “Our comprehensive community health strategy equips over 170,000 health promoters with tools, including smartphones, to upload vital information to government systems. AI integration will empower these workers to deliver specialized care at the village level.”

AI’s potential in breast cancer detection is undeniable. By combining technology with human expertise, the future of healthcare in Kenya and beyond could be revolutionized, ensuring more women like Judith receive the timely care they need.

For Judith, AI’s promise is bittersweet. “They say AI can detect cancer early, even before a lump form,” she says wistfully. “If I had access to that, maybe I would still have both my breasts. Maybe my children wouldn’t have to see me like this.”

Despite her struggles, Judith is determined to raise awareness. “Please, don’t wait. Go for checkups. Even if you feel fine, go. Early detection can save your life—and your family.”

Judith’s journey is a testament to the importance of awareness and timely intervention. As Kenya continues to embrace AI in its healthcare system, stories like Judith’s may one day become a thing of the past, replaced by tales of survival and progress.